recollected

stories about the things it would hurt to lose

--Contact: recolllected@gmail.com

The Poetry Book

This in-person interview has been transcribed.

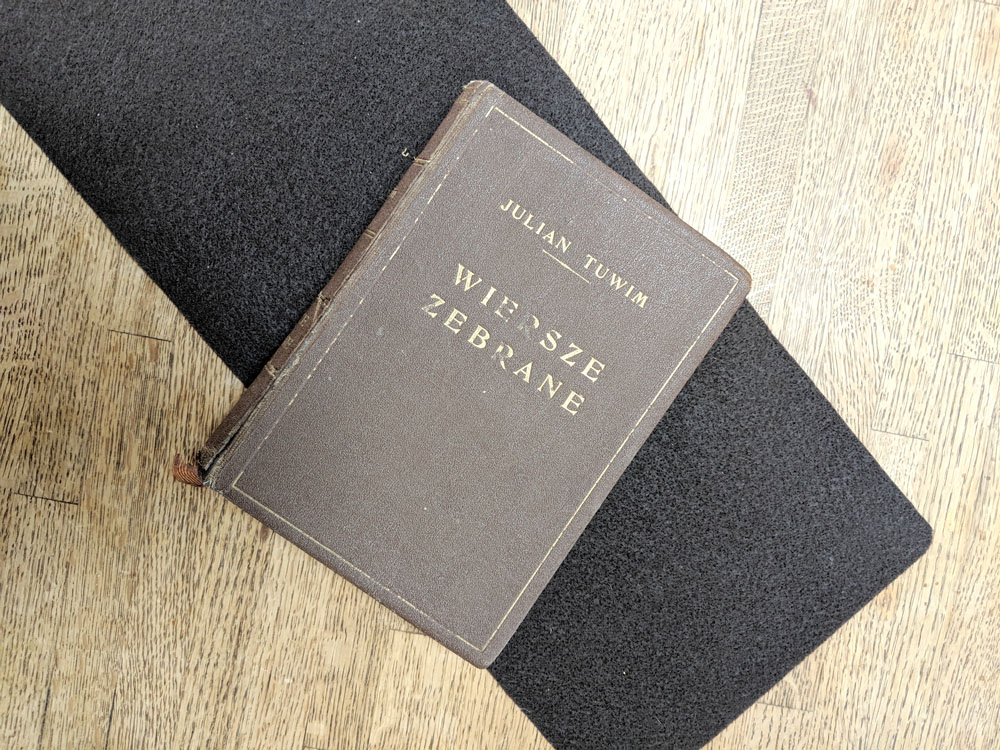

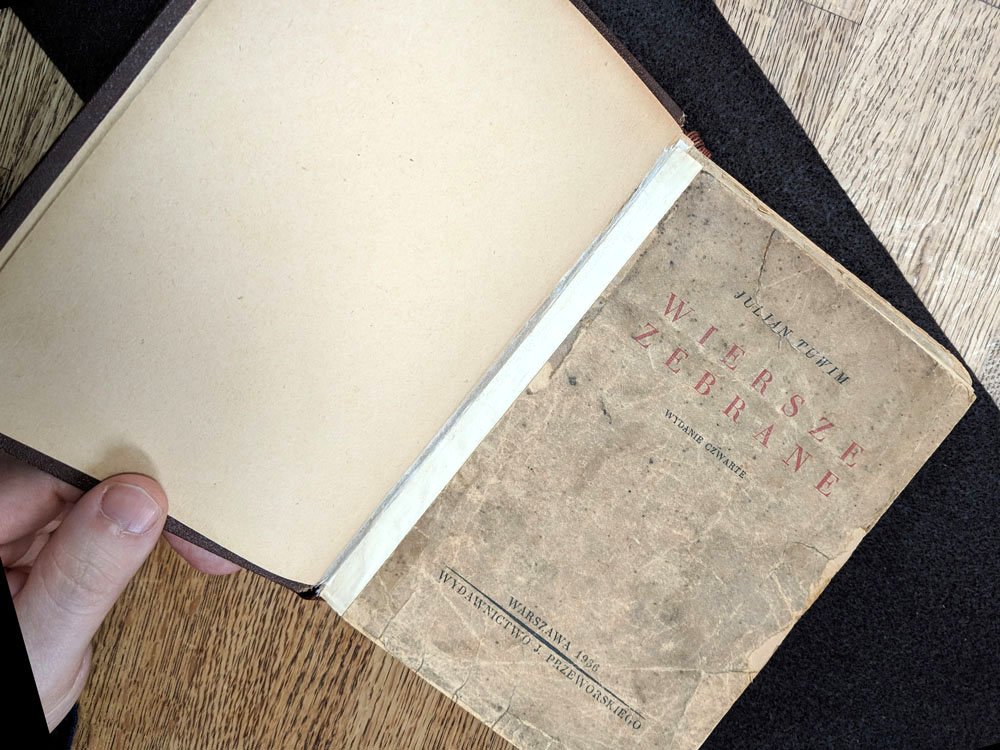

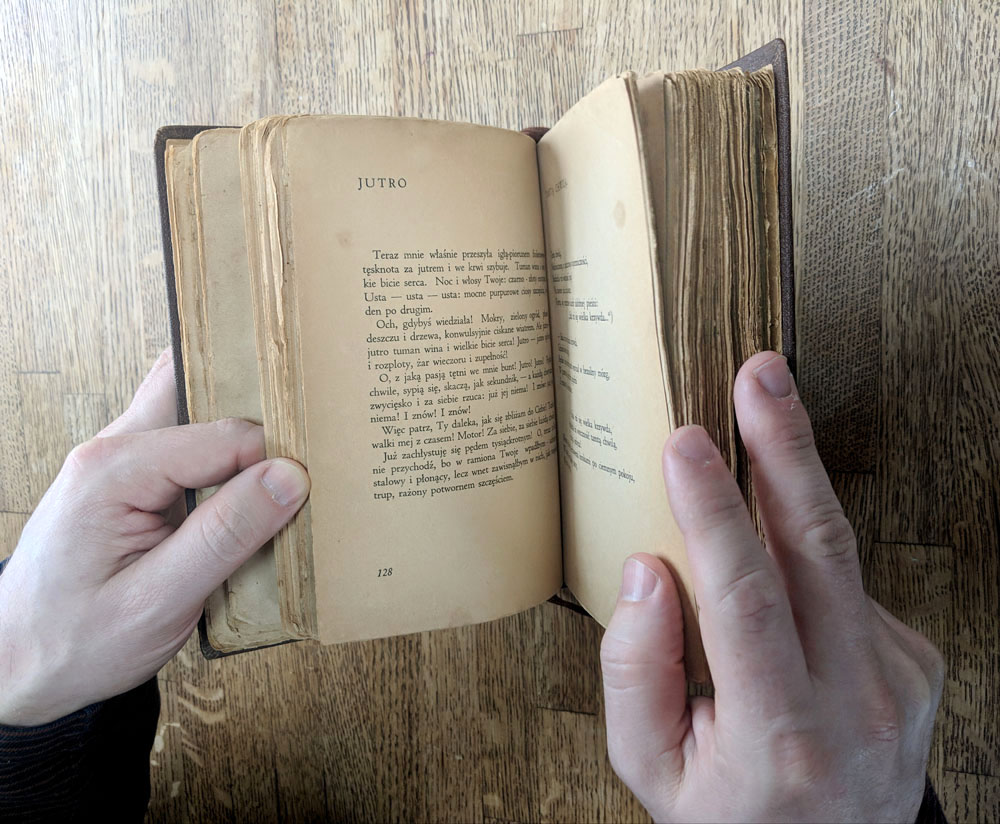

This is a book that was printed in 1936. It’s a book of collected poems by Julian Tuwim who is a very well known and beloved Polish poet, and also a hero in the Polish punk scene today. But this was a different scene in the ’30s.

This book is very important to me because it belonged to a very close friend of mine named Anita Leyfell who died this year about four months ago at the age of 102. She was born in 1917 and was from Warsaw originally. She lived in Warsaw during the Nazi invasion in 1939. When the Nazis invaded in ‘39 she and her mother escaped by foot, just left Warsaw with pretty much whatever they had on their backs, and walked east without really much of an intention except for trying to get ahead of the invasion. What ended up happening in that story is that they got to Bialystok and her mother who was older obviously and did not want to continue on with the escape decided she was going to go back to Warsaw. Obviously that was a tragic mistake on her part and she didn’t survive the war during the Nazi occupation of that city. But Anita, who was twenty-two and probably had a sense of the menace that the Nazis posed decided not to go back to Warsaw, continued to travel in the East.

She told me a lot of Poles who were trying to escape Poland basically were stateless people without papers and the Russians would arrest them and would take them to labor camps in Siberia because [the Russians] needed a lot of labor during the war. Anita was one of those people.

I forgot what city she was actually in when she got rounded up and taken by the Russian army to Siberia to work in the labor camp. Incidentally she was actually very — you know, we think of a labor camp in Siberia as a very bad moment in your life — but she was actually very grateful for this because it was a much better fate than staying where ever she was going to be in Poland. So this is sort of a long story to say that she spent the war in this labor camp in Siberia, it was a saw dust factory, I’m not exactly sure what that is, that’s how she described it.

While she was in this camp, she was able to get mail from her family every few months. Her sister was actually in Poland but had to cross the border to Ukraine in order to send packages, it was a laborious process of sending mail during the war.

…this was like her passport, this was the thing that connected her to her country that no longer existed.

[Anita] was able to occasionally get packages when she was in this labor camp, and usually what she would get is some kind of food, I think she said it was usually a can of beans or some sugar. Or occasionally clothing. If you got clothing, that was something you could trade, but it was also something you were afraid would get stolen. If you got food, you pretty much just ate it right on the spot. That’s how she described it.

But she decided that she really wanted something else that was very important to her. She wanted a book of poems by her favorite poet, Julian Tuwim. So she sends her sister a letter asking her for this. And then just forgot about it. Months and months went by, and she just forgot about the request. And then one day she got a package that was not a can of beans, and she opened it up and it was this book I have here. It was a nice, thick book of poems, something she hadn’t seen in a long time. It also was something that meant a lot to her because when she got to this labor camp, the Russians very gruffly told her and all the other Poles that were in this camp — “Poland is no more”. It was their rhetoric, “give up on the past, give up on whoever you are, give up on your identity, your national identity.” Because now you’re just going to be working for us. So it was part of their imprisonment, was being told that they no longer had any kind of Polish connection to Poland or to the place where they were from. So the way she described getting this book, besides the fact that it was just a pleasure to read and she was sort of able to luxuriate in the language of this pre-war imagery, of this totally different world that was gone, she said that the book itself was sort of her identity papers. Because her Polish papers were useless at that point. So this was like her passport, this was the thing that connected her to her country that no longer existed.

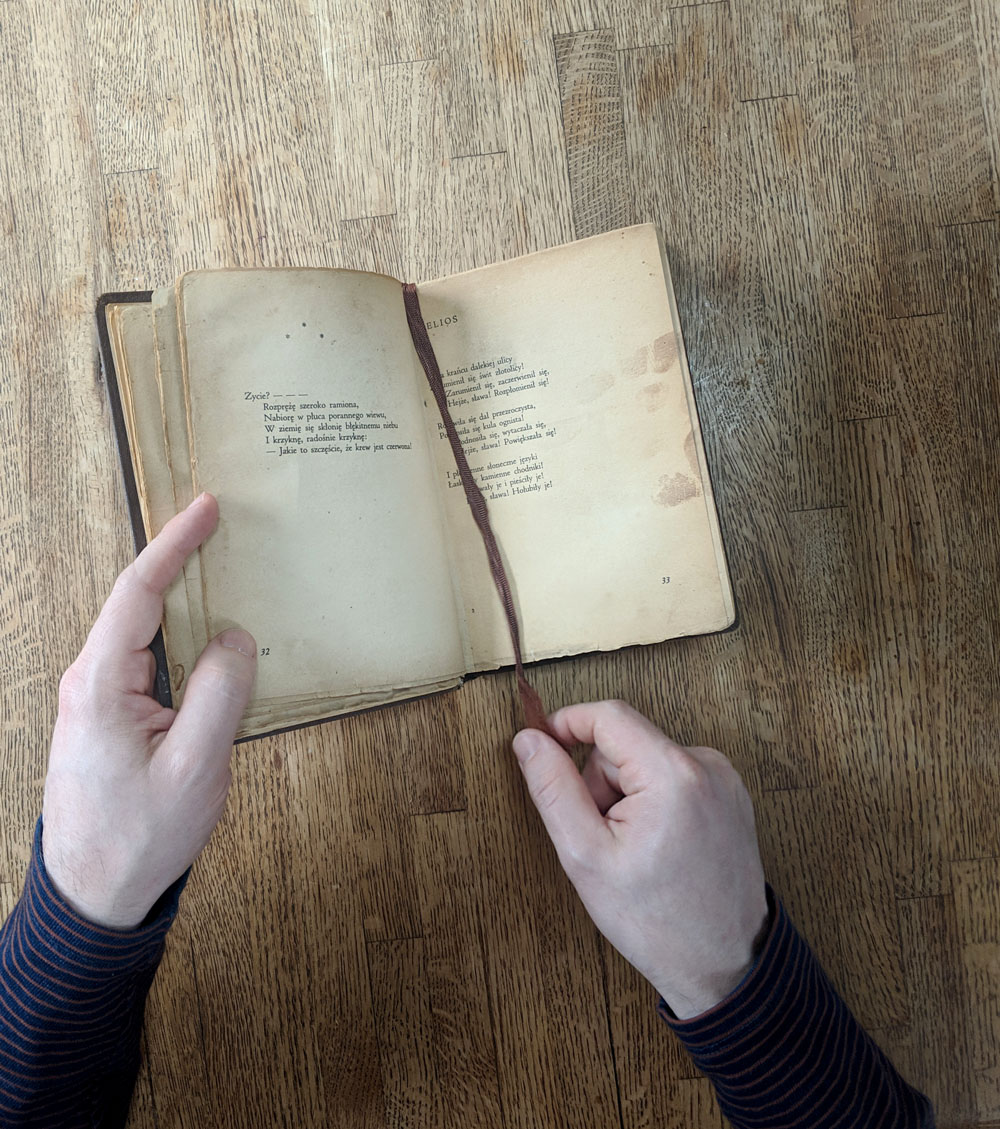

[Anita] joked that this book was so valuable to her, but actually didn’t have a lot of value in labor camp terms — it wasn’t the kind of thing that she needed to protect, or [that] people would try to steal from her, she could kind of just hold it. And she described how people would look at her in amazement that she was just sitting there reading. It wasn’t the kind of thing where people would sit around and read all that much. So it just sort of — everything about this book was completely out of place in this setting.

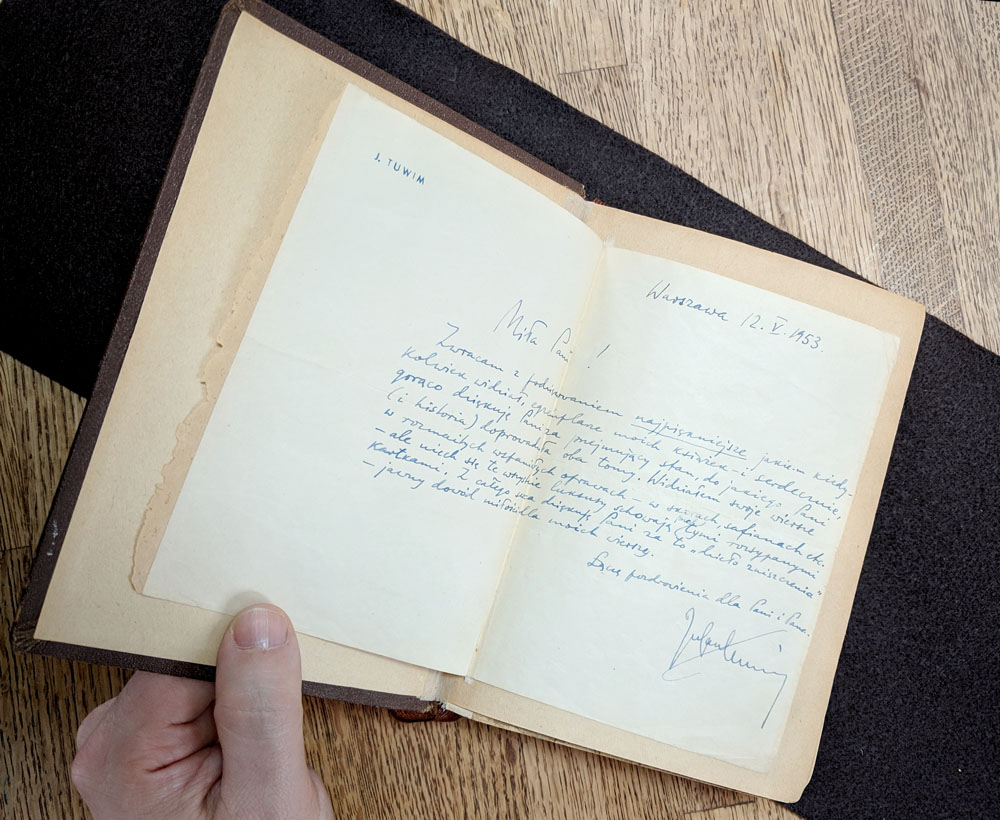

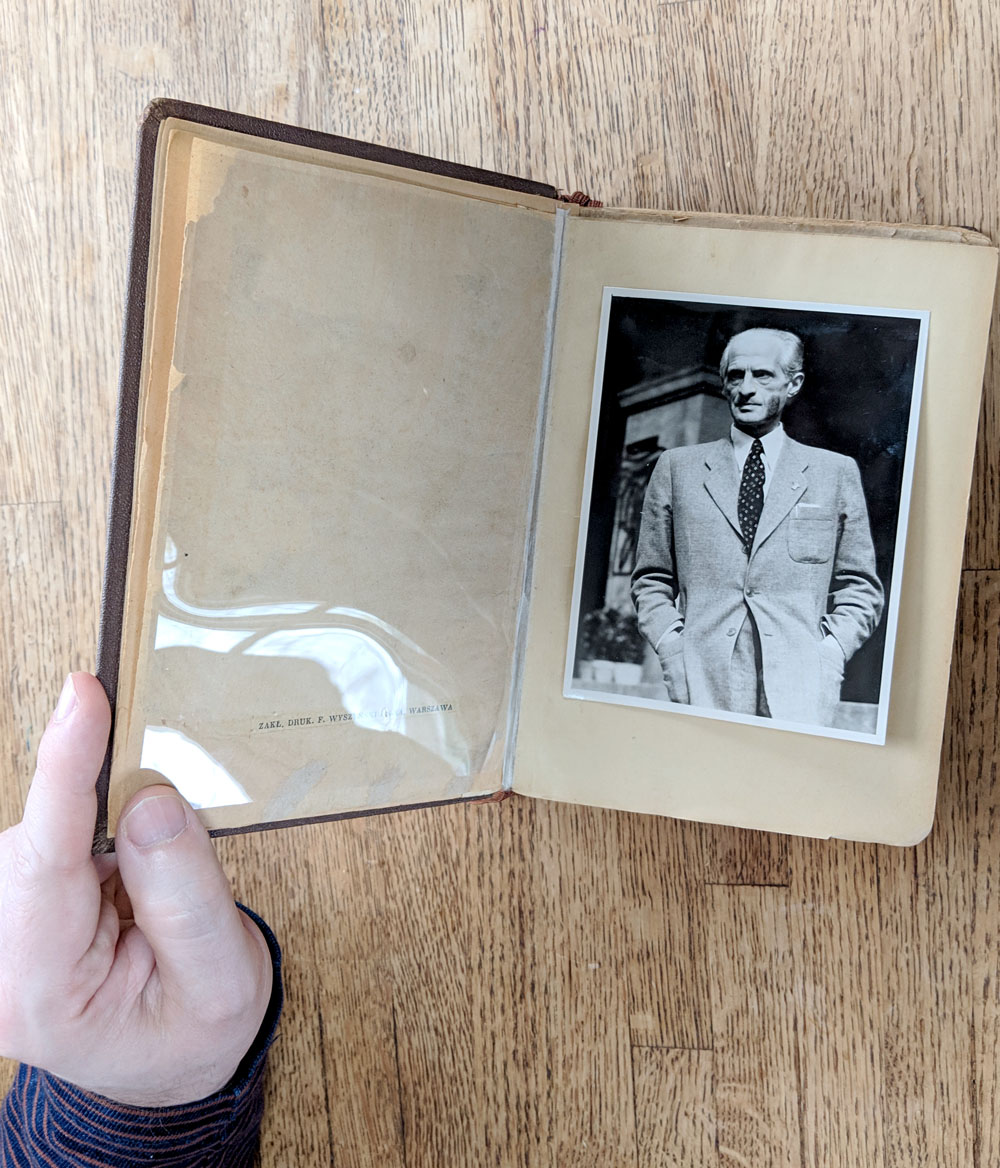

Long story short, she kept this book throughout that experience. She and the other Poles were actually liberated before the war was over, there was a deal cut that the Poles would be able to be released from the camp with the idea that they would actually help and fight in the cause against the Germans. So they returned back to their homes, although that was a long road also. A lot of traveling, a lot of different stops along the way, before [Anita] could get back to Warsaw, but she kept this book with her that whole time. In an amazing turn when she got back to Poland, got back to Warsaw — and this was, you know, exactly how we see in the pictures, the city was literally in ruins, people were just wandering around looking for each other, looking for anyone who’d survived, so it was that kind of setting — within five or ten years, she discovered that she lived on the same street as the poet Julian Tuwim. She was his neighbor. So they actually got to know each other a little bit. [Anita] told him this story about how important this book of poems was to her, and he wrote her a letter. He said in this letter that he’s seen many beautifully produced editions of his poems but this tattered old edition is to him the most beautiful. So that obviously meant a lot to her to be able to get that confirmation from the poet.

Can you describe it?

It’s a sort of cheap edition of this. I wish I could say a little bit more about what the actual materials are, but it’s certainly sort of an old, yellowing pages sort of edition, frayed along the edges. Later in life, Anita had it refurbished professionally by museum curators, so it’s actually in very good condition in that sense, it’s actually very readable. It’s sort of an old, cheap edition of this book. [Anita] had a photo of Tuwim put into it, and also the original letter that he had written to her inserted into it. But still pretty thin pages, it’s still falling apart.

How long has it been in your possession?

Just since she died. It was in her house, this was a very important object to her obviously throughout her whole life, so it only came into my possession after she died. I also have a slightly personal connection to it in the sense that she was a friend of mine, but I also helped her write her memoirs a few years ago. She was a writer and journalist herself. She wrote a chapter about this story that I just told [with] the story of the Tuwim book in her book, and I worked with her on that. So I sort of have a little bit of a connection to this book for that reason. She wanted me to have this book. But yes, it’s been a few months.

What does it represent to you now that you have it?

On the one level it’s a connection to her, she was a good friend of mine. This was a very important piece of her life. She moved all over the world and helped all of these people who lived different lives, these really intensely different lives over the course of her long single life. But this was one of those things that connected the different pieces. It went around with her for many, many years. And obviously as a writer myself and as someone who values the written word and the published word, and puts a lot of stock in the connection that people make through books, this is one of those really special editions where you can’t even imagine just how important writing can be to someone else. This is one of those unique cases where it matters. As a writer it’s very important to see books like these.

Where does it live in your home?

Right now it’s just on my bookshelf with my other books. I kind of like the idea of it just being there with the books and not necessarily being an object, a museum piece. I kind of just want it to be on the shelf in its natural habitat.

What would you feel if you lost it?

Oh my God. If I lost it… I would have my work cut out to find it. Oh you don’t mean misplaced, you mean if it was gone. Well, it served a good life. It had its purpose, I think it’s important to realize that. It was her book, and it stayed with her until the end, and I can rest assured that that was the most important life that it lived. So I feel good about that. And the other thing is that she wrote a very beautiful chapter about this book, and it will live on, and it’s very hard to destroy stories like that. So the story in its detail, in her words, will continue to live on. I would be able to take comfort in that.

tags: book - poetry - Tuwim - WWII - labor camp - Poland - Russia