recollected

stories about the things it would hurt to lose

--Contact: recolllected@gmail.com

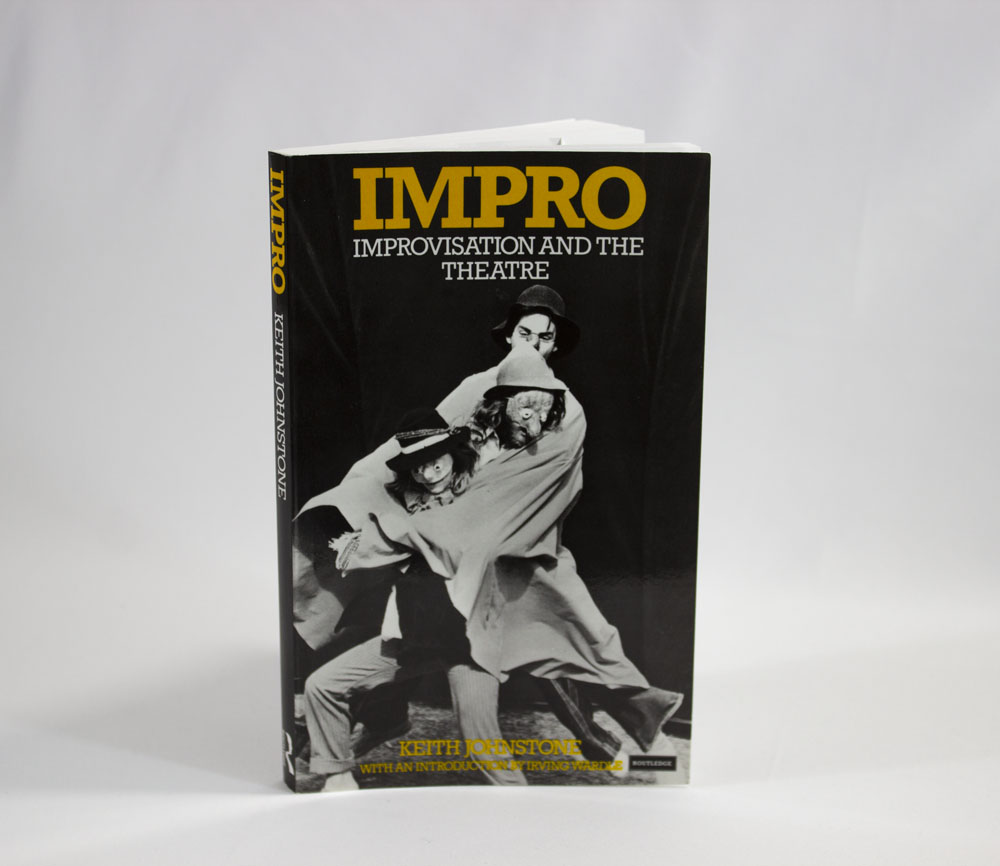

The Book

This in-person interview has been transcribed.

What is it: A book, Impro by Keith Johnstone

Where does it live: Any surface that’s on hand. It doesn’t go back on the bookshelf

What is it?

It’s a book called Impro by Keith Johnstone. Keith Johnstone is a guy who started improvisation in the UK in the 50s and 60s and this book is published I think 1980.

Ostensibly it’s about making interesting theater. Creating it, writing it, performing it. In actuality, the way that he gets to that place is he goes, sort of in a roundabout way, [by asking] what is interesting to people — what is interesting to an audience.

And he noticed that people who watch the show, they’re — whatever. Maybe it’s good, maybe it’s not. But something happens on stage that is not in the piece. Maybe somebody drops something. Now everyone leans forward in their chair, and they’re like, what’s going to happen? Are they gonna pick up the thing? Are they gonna break out of character? It’s like real life intrudes, and then people are interested. People are interested in real life. So how do we bring that on stage? The book ends up actually being about real life.

This looks like a new copy. How many copies have you gone through?

Five or six copies.

What happened to them?

Some were loaned and never given back, one was lost.

How did you get the first one?

The very first one was not my copy, I took it. I got my first copy of this book in the improv troupe I was in in college. I was 18 or 19. The improv troupe had a metal money box that had all of their materials in it. So that was lists of improv techniques, cash, miscellany, a bell for games, and like two books. Truth in Comedy, which sucks, and everybody has it, and Impro.

You could have chosen anything at all to talk about, why did you choose a mass-produced book?

I’ve said to people before — it’s sort of more fun to say than true — but it became my bible when I stopped believing in the bible. A lot of principles [in this book] helped me to find my way out of the hedge maze of Evangelicalism.

The specific constraints that my religious upbringing gave [to] my perspective on things like imagination and art, this Impro, Johnstone’s ideas, acted like a tunnel that I was able to [use to] climb out. I kind of had to like…(gesturing) hands and knees on my way out.

It had this framework in it that felt so right and resonant, and I never came across any piece of a thing that rang so true.

In my upbringing, I was, you know, Hellfire-level responsible for the content of my imagination. How [did] Jesus phrase [it]? “If you lust after a woman in your heart, it is the same as committing adultery with her”. That one line weaponizes the entire schema.

So reading this, [Johnstone] has got a very gradual way of opening that idea. What matters is what you say and what you do. How it affects people. And then of course what you choose to focus on, that can keep the brain going down certain roads, etc. But just things being in there, those are just in there, you can’t make a judgement call on [them]. And he connected that with — good improv is just connecting in the moment. Not trying to be clever, not trying to be funny, not trying to be overly paranoid how people see you and that’s with stuff like sexuality, and death, and all that stuff. It’s kicking around there, and he’s like, you cycle through it, you get through it.

To me that’s what was really meaningful about it. It wasn’t like, “you are forgiven”. It was like, “you are”. let’s drop that last word.

You’ve lost this book and there are no more copies, so you can’t get it back. What would that feel like?

I’d feel sad that it wasn’t out there in the world, but I’d also feel the obligation to proselytize what I’ve read.

tags: improv - comedy - evangelicalism - religion - impro